Understanding the Roots of the Younger Generations’ Despair in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq

Draw Media Shivan Fazil-Arab Reform Initiative People take to the streets for celebration after the controversial unconstitutional referendum for an independent state of Iraqi Kurdish Regional Government (IKRG) on 25 September 2017 in Erbil, Iraq. The non-binding unconstitutional referendum were took place in areas under the control of the Kurdish Regional Government (IKRG) in northern Iraq. © Hamit Hüseyin - Anadolu Agency Following the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq, the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) was for many years hailed in the west as “the other Iraq” for its relative peace and prosperity. Two decades on, however, the KRI has started to share the same governance challenges that grip the rest of the country; dashing the hopes of an entire generation that grew up and came of age under the Kurdish self-rule with little to no memory of life under the previous regime. Young people’s needs and demands for quality education and employment are repeatedly not met, and as a result, youth disenchantment is mounting. This unprecedented moment of pressure on the region’s youth is rooted in an economic slump that is frustrating the aspirations of youth, who are forced to bear the brunt of decisions they have no part in making. In addition to economic factors, youth political participation (or lack thereof) is also playing an important role. Policy-making processes are not inclusive and participatory due to the waning interest in politics and insufficient participation and inclusion of youth. Hence, socio-economic policies and plans are not in line or responsive to the needs and aspirations of a young and steadily growing population. Consequently, dissent and despair have been on the rise since the fraught 2017 independence referendum despite the authorities' efforts to constrain protests. In 2022, for the second year in a row, university students across the governorates of Sulaymaniyah and Halabja staged week-long demonstrations and boycotts demanding the government reinstate a small monthly stipend, improve housing conditions, and reduce tuition fees. In 2021, university students took to the streets demanding the restoration of monthly allowances that were cut in 2015 as part of the Kurdistan Regional Government’s (KRG) austerity measures. The year before that another largely youth-led protest wave had erupted in Sulaymaniyah before it soon spread to the far-flung midsized towns where the impact of economic crises is particularly severe. The rhetoric compared to pre-referendum protests was maximalist with demonstrators calling for an end to the two-party rule political system. The demands of the 2022 and 2021 protests nevertheless brought tens of thousands of students to the streets. The fallout from the referendum which included, amongst other things, the setback in the disputed territories and diminished leverage vis-à-vis Baghdad was seen as the failure of the political elite to advance the Kurdish national ambitions. It also gave impetus for the more maximalist narrative in recent demonstrations and calls for the overhaul of the two-party rule in the KRI. The rage and rhetoric of the demonstrations, however, were also used as a pretext by the government to dismiss youth protests as illegitimate, further widening the gap between the youth and the authorities. Young people are not only expressing their frustration through street protests: steady streams are also risking their lives in the pursuit of a better life abroad. In November 2021, images of Kurdish migrants from Iraq, primarily the youth, stranded at the Belarus-Poland border grabbed the international headlines. They had taken the perilous journey due to persistent and increasing unemployment and loss of hope, despite the region’s oil riches. Therefore, the socio-economic situation that shapes the demands and aspirations of the youth is key to understanding growing disillusionment and dissent in the KRI. ‘A golden decade’ The future looked bright for the Kurds in Iraq after the turn of the millennium. They had endured genocide and the effects of crippling economic sanctions over the previous two decades. However, while the rest of Iraq drifted into chaos after a 2003 US-led invasion toppled longtime ruler Saddam Hussein, the KRI remained quiescent. It enjoyed relative peace and stability and embarked on a decade of economic boom. The Kurds who were the big winners from the regime change began to hope. The Kurdish population was promised by the ruling parties that their share of the federal budget and oil revenues from the newly developed oil wells in the region, could replace the impoverishment of the preceding decade. In 2009, the start of Kurdistan Region oil exports was declared by then President Massoud Barzani as “a historic date” and “a giant step” and promised that “this achievement will serve the interests of all Iraqis, especially the Kurds.” The new access to oil wealth, which had previously been inhibited by international sanctions and locked up under the control of the Ba’ath regime, began to fund sprawling gated communities, shopping malls, and private schools in the region’s largest cities, widening the income gaps between the different social classes. The political leadership’s aspirations to turn the regional capital, Erbil, into the “next Dubai” seemed to be fast becoming a reality. People, young and old, believed the promise. However, the adopted economic model was at the expense of the policy considerations and development priorities of the future generations. The KRG provided free education and healthcare, subsidies for fuel, and jobs in the public sector – offering employment in exchange for loyalty and acquiescence. It extended loans to support private enterprises and housing mortgages to its citizens. The public sector became the single largest employer to absorb the tens of thousands of young graduates entering the job market annually. New jobs were increasingly created in the public sector rather than the private which was still quite small. Living conditions improved at a rapid pace. The economy grew considerably thanks to oil rents and public investment. The government’s annual budget increased from $2.5 billion in 2005 to $13 billion in 2013. The outcomes of this economic model, in the short run, were low and declining inequality, low poverty, and to some extent, shared prosperity. In the long run, however, funding the salaries of this bloated and inefficient public sector has become a real burden and a challenge given oil price fluctuations. These developments ushered in and greatly shaped the current social contract between the rulers and the ruled, where the political elite defined politics based on Kurdish identity and nationalism, or Kurdayeti. It was in this context that a frail and fragmented social contract was put in place, shortsightedly focusing on the provision of universal education and health as well as visible welfare interventions and employment without ensuring the sustainability of this model. A fundamentally broken social contract Several aspects of this social contract have begun to fray since 2015. First, because of economic recession, owing to the war with the so-called Islamic State, plummeting oil prices (between 2014-2016 and again in 2020), and to protracted revenue-sharing disputes with the federal government of Iraq. The public sector could no longer absorb the thousands of young people entering the job market each year. The KRG since 2013, which last had a budget law, slashed public spending which included salary cuts and a hiring freeze, and, in doing so, delivered a major blow to an entire generation that expects employment and benefits. They believed that if they obtained a university education that they would find a job; instead, they were suddenly faced with the prospect of competing for elusive opportunities of employment. The long-standing skill mismatch has not prepared them with the skills suited for the job market. Youth unemployment and idleness have soared – the total rate of people aged 15-24 who are not involved in education, employment, or training is 30% (20% for males and 40% for females). The overwhelming sense is that most employment opportunities are based on one’s political and social connections rather than merit. Second, the lagging growth in the private sector is also connected to the nature of the region’s political economy. The rapid development of some sectors such as the natural resources and real estate sectors at the expense of the more productive and labor-intensive sectors, a phenomenon that is known as the Dutch disease, has weakened the region’s economy and inhibited the growth of others such as manufacturing and agriculture. Relatedly, politically connected conglomerates benefit from generous rents and deals that undermine competition, entrepreneurship, and job creation. The most lucrative sectors, such as the real estate, telecommunications, and oil and gas tend to be dominated by companies that are owned by or connected to the ruling parties. The private sector growth has remained insufficient to absorb the surplus labor. In addition to the aversion to work in the highly unregulated private sector where the pay remains low despite the long hours. Worse still, like the rest of Iraq, the KRI has not escaped what is called the “resource curse”: it has ended up with less economic growth, less democracy, and less social equality, not despite the abundance of natural resources but because of them. Third, nearly a decade of austerity has precipitated the rapid decline in the provision of basic services – especially healthcare and education. These sectors are not only vital in people’s daily lives but are also, along with the security services, the most important public sector employers, especially for women’s labor force participation. The government still provides basic education and healthcare, but the quality of these services has declined. Protests and strikes against unpaid salaries, along with the lack of teaching and medical staff, have further deteriorated public service provision. The COVID-19 pandemic, which compelled hospitalization and homeschooling, barred many from a meaningful learning experience and exposed the substandard condition of the vital health and education sectors. People are forced to resort to private hospitals/clinics and schools for better healthcare and a more meaningful learning experience. Moreover, poor public service provision has created a lucrative market for private education and healthcare. This has forced people to pay for the same services to which they are already entitled in order to get them in better quality. For instance, the aspiring middle class is driven to send their kids to private schools and universities to learn skills in the hope of increasing their competitive advantages in an increasingly tight job market. The outcome has been a growing sense of social inequality and injustice, which is acutely felt by young people who bear the brunt of its consequences. All of these factors have contributed to rising dissatisfaction with the government to the point that street protests are a regular occurrence, albeit limited to the eastern part of the region. Recent protests have also become increasingly violent because of the authorities’ securitization of public space and growing intolerance of dissent. The unspoken deal at the heart of Kurdish politics in Iraq has been that the ruling parties control the political space but, in return, they deliver a better life. However, the austerity policies pursued since 2015 have reversed the improvements in living standards. Moreover, the region’s economic development model adopted in the preceding decade has made many people feel left out and with elusive prospects of social upward mobility. It has also contributed to rising public dissatisfaction and disenchantment with politics, while the region’s population is ever more disaffected and struggling to make ends meet amid soaring inflation and a cost-of-living crisis. The way forward The highlighted trajectory points to a clear indication that the current situation is unsustainable and requires a course correction. Renegotiating or redrawing the social contract has become a necessity to realign the relationship between the government and society and the obligations each has to the other. The public sector should be reformed to ensure the provision of the basic services that the government is expected to deliver. This is central to meeting citizens’ expectations of the government and enabling the emergence of a more balanced and durable social pact. The reimagined social contract must protect the most vulnerable such as the low-income earners and stimulate human capital development. A major challenge is to overcome inter-party squabbles that compound the region’s governance issues and to address patronage and nepotism. There are some promising developments as socio-economic concerns have become catalysts triggering the surge in entrepreneurship and activism, which indicates that the new generation is willing to break away from the patronage system. It is also embracing a citizenship model that is more inclusive and allows greater rights and responsibilities for citizens. They have formed new platforms, ideas, and dreams to push for a more just and prosperous future. These positive signs, however, are highly constrained by the system in which they operate and represent glimmers of hope rather than broad rays of progress. Across the board, talents can be found waiting to be tapped, entrepreneurial flair ready to be unleashed, and young people impatient to be given their chance. They are being held back by the region’s broken economy and broken politics. They also lack opportunities to engage with the political process and thus often turn to other non-political means to articulate their demands and express their dissatisfaction. There is also a growing fatigue with the region’s two ruling parties in charge since the inception of the region in 1991. The record low turnout in recent elections is an indication that they have lost faith in bringing about change in the status quo through conventional means. Abstaining is also a political decision. It is, therefore, imperative to address the waning interest in politics and facilitate youth engagement and participation in the political process. To be sure, while the KRI’s ruling parties hold the federal government in Baghdad responsible for the economic slump, the younger generations anticipate jobs, services, and opportunities, not from the Government of Iraq, but from their own rulers in the semi-autonomous region, who presided over its rise and prosperity, but have signally failed to ensure its fair and equitable distribution. Indifference and failure to heed the demands and frustrations of the young population will likely lead to more resentment that could bring the kind of unrest that other parts of Iraq have faced in recent years.

Read moreThe Rise and Fall of Kurdish Power in Iraq

washingtoninstitute- by Bilal Wahab Despite thirty years of landmark achievements, the KRG’s endless quest for economic independence has only entrenched its internal divisions and kleptocracy while shifting its dependency—from Iraq to Turkey, and from foreign aid to oil revenues. If the 1991 Gulf War led to the birth of the Kurdistan Regional Government, the US invasion in 2003 propelled it into the future. At the start of the invasion, Iraqi Kurdistan served as the northern front of the war, elevating the status of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). The destruction of President Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime buttressed Kurdish rights and enabled their political and economic power to grow. Compared to the violence and sectarian strife that befell the rest of the country under the US-led occupation, the Kurdistan Region of Iraq was held up by the US pundit class as a “safe haven” and “island of decency”—a narrative the KRG encouraged with a public relations campaign describing Kurdistan as “the Other Iraq.” 2003 brought with it a unity of purpose among Iraq’s Kurdish parties. They capitalized on their longstanding relationship with the United States and Britain, the primary enforcers of the no-fly zone following the first Gulf War and the two major proponents of regime change in 2003. Although differences persisted, Kurdish parties spoke in unison in Baghdad, particularly in the early years following the invasion. They worked to enshrine their new powers and rights into Iraq’s 2005 constitution, which recognized Kurdistan as an official region and granted the KRG power to govern largely independently of Baghdad. Kurdish parties also fully supported the 2005 parliamentary elections. As a result of these efforts, they gained a significant influence within the Iraqi state. Kurdish members of parliament form a significant block that often makes or breaks governments and legislation. In the muhassasa system—the informal but persistent practice of ethno-sectarian division of top jobs—Iraq has only had Kurdish presidents since 2006. Ethnic Kurds have on occasion served as deputy parliament speakers and led key ministries such as finance and foreign affairs. But working within the state apparatus has confused the Kurdish role in Baghdad. On the one hand, the KRG has sought the greatest possible share of the state’s powers and revenues. On the other, given historical Kurdish fears of a strong central government, they have also invested in their ability to secede, exemplified by the referendum for independence in 2017. Today, Iraqi Kurdistan faces external challenges, most notably a legal and financial squeeze by Baghdad’s federal government and threats of Iranian and Turkish attacks. The real threat to the KRG is not external, however. Thirty years after its founding and 20 years on from the US invasion, the KRG—as if going through a mid-life crisis—lacks a clear vision for its future. Amid the threat of losing relevance, it stares at implosion due to economic uncertainties, chronic internal divisions and weak institutions. Finding Wealth Kurds in Iraq have long based their struggle for self-rule on their grievances as a persecuted ethnic minority. Kurdish rulers gained legitimacy by standing up for Kurdish rights. Following the first Gulf War and the 1992 elections, however, such revolutionary credit gave way to democratic legitimacy. The elections gave birth to the KRG and brought two parties, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), to formal political power. Since then, each of the two major Kurdish parties has remained inextricably associated with a family—the Talabani family lead the PUK, and the Barzani family the KDP (their second and third generations, respectively, are currently at the helm of power). The civil war in Iraqi Kurdistan between 1994 and 1998 discredited both parties, dividing the region into two single-party fiefdoms that persist until today. Meanwhile, over the course of the past two decades, as a new generation of each ruling family took on the mantle of leadership, their legitimacy has lacked both revolutionary and democratic standing. Economic development emerged as an alternative. Indeed, between 2004 and 2014, the KRG translated post-invasion opportunities into an economic boom. A construction frenzy in this period caused the capital city of Erbil to more than double in size. The KRG says it has rebuilt 65 percent of rural Kurdistan that was destroyed during the Anfal campaign of ethnic cleansing in 1988. Two of Iraq’s three national cell phone companies are headquartered in Kurdistan, and the region is also home to a slew of hotels, gated communities and private schools, including two American-style universities. By 2005, the KRG had built two international airports, in Sulaymaniyah and Erbil, unshackling the landlocked region. Foreign visitors could obtain visas upon arrival, a policy that the Iraqi government did not adopt until 2021. Mass public hiring decreased unemployment, although foreign laborers filled much of the skills gap. Furthermore, a 2006 investment law, which offered investors perks such as land ownership, tax holidays and profit repatriation, helped the KRG attract significant local and foreign capital. Today, there are over 3,000 foreign companies registered in the region. On the diplomatic front, the KRG hosts 42 consulates and maintains 14 representation offices around the world. Making the most of its geographic location and security, Iraqi Kurdistan has become an important regional trade route and destination. Turkey, whose only land border with Iraq goes through the Kurdistan region, is the KRG’s largest trading partner. In 2017, the volume of trade between Turkey and Iraqi Kurdistan was $2.5 billion, representing nearly one third of Ankara’s overall trade with Iraq. Similarly, one third of Iraq’s imports from Iran—an estimated $2.4 billion a year—are to Iraqi Kurdistan. Moreover, 50 percent of Iran’s exports to Iraq pass through border crossings controlled by the KRG. From Foreign Aid to Oil Federalism The federal system proposed in the 2005 constitution granted the KRG a significant role in managing the oil and gas resources of the region. These provisions served as a safeguard: Should the new Iraq fail, it would be possible for an economically independent Kurdistan to take the next step toward statehood, the penultimate nationalist dream. The constitution envisioned a system of petro-federalism, in which the federal Iraqi government and the KRG would share responsibility over oil policy and revenue. But in the years since its ratification, the Iraqi parliament has consistently failed to pass a national hydrocarbon law that would regulate the energy sector and define these joint roles. Acting proactively, the Kurdish parliament passed its own natural resources law in 2007 and started inking some 55 contracts with international oil companies. While the federal government maintained that this law was unconstitutional and the oil contracts illegal, the KRG pushed ahead. It adopted production-sharing contracts, an industry favorite, which allowed international oil companies a stake in the region’s petroleum assets. This “smaller, faster, lighter” approach, as Deputy Prime Minister Qubad Talabani put it in a 2012 interview with the author interview, helped jumpstart the Kurdish energy industry. Small firms, or wildcatters, came first, but Big Oil soon followed. In 2011 and 2012 ExxonMobil and Chevron each signed exploration contracts with the KRG, materially boosting the legal standing of its energy industry. The KRG asked for neither permission nor forgiveness from Baghdad, an approach that in many ways paid off. By mid-2022, the KRG was producing nearly 450,000 barrels of oil per day, most of it exported via the region’s independent pipeline through Turkey. In the second quarter of 2022 alone, Iraqi Kurdistan’s oil sales earned $3.77 billion in gross revenues. While only 41 percent of these revenues made it into KRG coffers (the rest was dedicated to paying the oil sector’s costs as well as servicing its debts) the KRG still reaped $1.57 billion. As for natural gas, the KRG’s marketed natural gas production stood at about 5.3 billion cubic meters per year in 2021. The payoffs, however, have come with a cost. The federal government’s claim on Kurdish oil has forced the KRG to sell at a political risk discount. Furthermore, disputes between Erbil and Baghdad over oil and customs revenues boiled over in 2014, leading Baghdad to cut off the KRG’s share of the national budget. In 2022, the Iraqi Federal Supreme Court formally ruled that the KRG’s natural resource law was unconstitutional and its oil contracts and exports illegal. The Iraqi government had also sued Turkey in international arbitration courts over allowing the KRG to use the Iraq-Turkey pipeline without Baghdad’s approval. At the time of writing, the court favored Iraq’s position, compelling Turkey to halt the KRG’s oil exports. The future of the KRG’s independent energy industry remains uncertain. Intent on more independence from Baghdad, the KRG has grown dependent on other entities and factors beyond its control, including global oil prices, the dollar-dinar exchange rate and Turkey, through which its pipeline passes. The vulnerabilities of this system started to show in 2014, when the expansion of ISIS caused international oil companies to either withdraw or suspend planned developments. The KRG made up for the losses by taking over Kirkuk’s oil fields following the Iraqi army’s retreat, which doubled the KRG’s crude exports to 550,000 barrels per day. But these gains were hampered by falling oil prices. Per barrel, oil prices fell from a peak of $115 in June 2014 to $70 in December and to $35 by February 2016. Deputy Prime Minister Qubad Talabani described the KRG’s dire financial situation at the time as an “economic tsunami.” A telling manifestation of lost confidence in the KRG has been a renewed wave of migration to Europe. As a result of these factors, among others, by 2021 the KRG faced a debt of $31.6 billion. Internal Divisions and Institutional Weakness In recent years, fissures have cropped up among Iraqi Kurdistan’s ruling families, who have grown in prominence as the region’s political parties have weakened. After PUK founder Jalal Talabani passed away in 2017 his eldest son and nephew together took the reins of the party as co-presidents. In 2021, a feud broke out between the cousins, Bafel and Lahur Talabani, and the former ousted the latter. Meanwhile, on the Barzani side a power struggle is brewing between two Barzani cousins, which has the potential to disrupt not only the cohesion of the KDP but the entire regional government. These internecine struggles reflect broader institutional weaknesses and democratic regression in the Kurdistan region. As an example, KRG institutions were brittle and completely unprepared to weather the “economic tsunami” that began in 2014. The last time the KRG parliament had passed a budget was in 2012. The public sector had swelled uncontrollably, crowding out private sector jobs. By 2017, the KRG was the largest employer in Kurdistan, employing half of the labor force, roughly 1.4 million people, to the tune of $750 million a month. Corruption and inefficiency have marred public sector employment, with thousands of ghost employees, double dippers and undeserved pensioners, while the budding private sector owes its existence to holding companies owned or controlled by members of Kurdistan’s ruling families. To avoid showing its hand to Baghdad, the KRG energy industry has become increasingly opaque and unaccountable. The Peshmerga enjoy influence and prestige and have continued to garner significant public and political support, especially during their partnership with the US-led anti-ISIS coalition, but the cavernous political rift between the PUK and KDP has decreased the Kurdistan region’s value to the United States as a partner and diminished Kurdish leverage in Baghdad. There is no accurate accounting available, but the number of Peshmerga fighters is estimated to range between 160,000 to double that number. Prime Minister Masrour Barzani admitted that the Peshmerga forces have more generals among their ranks than either the US or Chinese military. Ever since the war against ISIS, the United States has provided stipends and training to Peshmerga units in exchange for the promise that the Peshmerga will be unified under the command of the KRG rather than its ruling parties. But the KDP and PUK refuse to surrender control of their respective units—a stance that Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces have cited in their own snubbing of national authority. Overall, the KRG’s reputation for valuing democracy and human rights has eroded in the years since 2003. Due to civil war and internal divisions in the 1990s, the region’s second parliamentary elections were not held until 2005, 13 years after the first election. Subsequent elections have taken place only following significant delays. Electoral victory and power are increasingly out of sync in the region. When the unarmed opposition party, Gorran, came in second in the 2009 elections, ahead of the PUK, the two ruling parties did not allow Gorran to share in power. Although President Masoud Barzani’s term ended in 2015, he only left office in 2017, effectively shutting down the Kurdish parliament for two years in order to extend his tenure. No wonder turnout has been steadily declining at Kurdish elections. The KRG’s Future Despite a persistent narrative of grievances and victimhood, Iraqi Kurds have exercised significant power and agency during the past three decades. KRG leaders continue to seek more power and autonomy, but to what end? Although they rebounded after decades of war, genocide and neglect, post-invasion Kurdish politics has not managed to shake off chronic internal divisions. The region’s most advanced institutions that could potentially support an independent Kurdistan remain its economy and Peshmerga forces. While the KRG has wielded economic policy to shift toward political independence, they have yet to produce a viable economic model. Indeed, despite 30 years of successfully managing a regional economy, the endless quest for economic independence has only ended up shifting dependency from Iraq to Turkey or from foreign aid to oil revenues. The ad hoc economic policy that has slowly emerged, like a Polaroid photo, over the past two decades displays traits of socialism, free markets and kleptocracy. Access to power and wealth, meanwhile, remains anchored to politics, not to economic activity. The 2017 independence referendum, called for by then-President Barzani, tested the Kurdistan region’s military and economic assets. Neither the international community nor the KRG’s neighbors could stomach redrawing the borders of the Middle East, and the KRG was not ready to withstand the economic and political costs of its push to secede from Iraq. The referendum and its aftermath cost the KRG the gains it had made following the ISIS invasion of 2014, including Kirkuk and its oilfields, which were reclaimed by Iraqi military and Popular Mobilization Forces after an armed encounter with the Peshmerga. Most damaging, however, was the clarity it bestowed on a hitherto ambiguous question: Can the KRG become an independent state? As Kurdish divisions deepen and security in the rest of Iraq improves, the balance of power that once favored the KRG is shifting in Baghdad’s favor. Since the referendum, KRG leaders disagree on visions for their position within Iraq and on plans to save their embattled energy sector. Should the Kurdish economy remain hinged on foreign aid, oil and budget transfers from Baghdad, or can it build a robust economy through reform and diversification? These are among the questions raised over the past 20 years. Whether and how they are answered will determine the Kurdistan Region’s future. Bilal Wahab is the Wagner Fellow at The Washington Institute. This article was originally published on the MERIP website.

Read moreWhy the United States should stop supporting the Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga

Diary Marif/ culturico The United States has planned to unify the Kurdish forces of Peshmerga, providing more financial aid and weaponizing them in order to defeat IS and other extremist groups. But the senior military men and politicians keep aside the weapons and aid for themselves and do not give them to the Peshmerga forces who are on the front lines fighting IS. Instead, they use weapons to repress the Kurdish protestors who ask for their basic rights and freedom of expression. In early August, the Kurdistan Region’s Minister of Peshmerga Affairs, Shoresh Ismail, met with U.S. officials in Washington DC and promised to follow through on reforms aimed at unifying the Peshmerga forces of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). The Peshmerga militias are the main forces of the KRG in Iraq, but they are not controlled by the KRG. Rather, they are governed by political parties. This issue of divided loyalty affects the KRG’s national strategies to protect Kurdistan and defeat extremist groups. For example, a few days after Ismail’s promising visit with U.S. officials, Mohammed Haji Mahmoud, the leader of the Kurdistan Socialist Democratic Party, illegally held a military parade for his militia without censure from the KRG. The militia may be under Ismail’s command, but the troops clearly listen to Mahmood, not the minister. Accentuating this general discord even further, Ismail returned from his visit with U.S. officials to brief not the KRG parliament, president, or prime minister, but rather the former President, Masoud Barzani, who has no official position or responsibilities in the current government. The KRG’s lack of control over the Peshmerga is proving a problem for U.S. partners. The U.S. has been in a partnership with KRG in Iraq to defeat the Islamic State (IS) and other terrorist groups. The separation of the forces, however, has negative consequences for U.S. plans. The U.S. also wants the Peshmerga to cooperate with the Iraqi army to set up robust security in the country. Mahmoud’s illegal parade and Ismail’s meeting with Barzani reveal an obvious, disappointing reality: the unification of the Peshmerga is just not happening, and any U.S. financial or political support for it instead goes into the pockets of the political parties’ militias, putting the lives of ordinary people at risk. Why is Unification Failing? The U.S. proposal of integrating and unifying the Peshmerga forces is not a new agenda. When the KRG formed in 1992, it bridged several political parties, including the two major ones: the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), led by Masoud Barzani, and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), led by former Iraqi president Jalal Talabani. Right away, these parties undertook a plan to abolish their partisan militias and set up a single national force to protect the region and its people (1). Although straightforward in theory, the plan caused chaos on the ground, and a bloody, four-year civil war broke out in which thousands of the Peshmerga were tortured, wounded, and killed. One dire consequence of the civil war was that the Peshmerga forces of the parties were not able to trust each other (2). To this day, they are still traumatized by the civil war years. Therefore, unification has not worked. During the invasion of Iraq, the U.S. high officers proposed to Talabani and Barzani to unify their forces under one national commander. Although Talabani and Barzani accepted the proposal, they hesitated to follow it, as each party thought that losing its militia would have a negative impact on its political hegemony and that losing control of its forces would affect their interests. But in 2010, both parties tried again and consequently integrated fourteen brigades, though this integration was only of about 40,000 Peshmerga fighters and over 120,000 troops remain in unintegrated KDP and PUK units. The process of integration was then halted again for two main reasons. Firstly, U.S. troop withdrawal from Iraq in 2011 meant less attention from the U.S. on integration; secondly, both parties were in a contest to win the fame of their militia against IS. The desire to unify the Peshmerga became more concrete in 2014 when IS began assaulting Iraq. At the time, Barzani was President of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). As commander-in-chief of all Peshmerga forces, he granted the Peshmerga minister, Mustafa Said Qadir, six months to carry out the necessary reforms in order to unify the forces against IS. Even though Barzani was the most powerful man in Kurdistan, his demand for reform has gone unanswered for the last eight years. Barzani’s demands have no power in the PUK-controlled zone, and his stubborn desire for the Peshmerga to stay under the control of his own party led to significant disruption and further division in the PUK zone and elsewhere. Although nominally united under one government, the bitter divisions between the KDP and PUK are just as deep-seated and intense now as they were when the PUK separated from the KDP in 1975. Having each established their own militias to protect their interests, the parties spent decades killing one another in the 1980s and during the civil war of the 1990s—a reality that cannot be easily undone. The wounds of past conflicts are still present in today’s parties, and any sign of friction nowadays is met with threats and the fear of another civil war. With such deeply-entrenched attitudes, Peshmerga forces simply do not listen to the Minister of Peshmerga Affairs and are instead loyal to political party leaders, protecting the interests of their party and competing against other parties. In return, the political parties incentivize the Peshmerga with monthly payslips and threaten them with firing or kidnapping if they refuse to act as protection to party leaders and their families. Even the fourteen brigades—consisting of around 40,000 Peshmerga fighters—that were nominally integrated in 2010 remained party-focused. In 2017, these brigades were once again separated as party tensions ran high during the Independence Referendum for the Kurdistan Region. The PUK troops withdrew from the disputed territories between Baghdad and Kurdistan and Iraqi forces replaced them. The KDP accused the PUK of collaborating with the Iraqi army and betraying the Kurdish cause, as the KDP knew the PUK and Iran had a secret agreement. The KDP claimed that Iran wanted Kurdistan not to be an independent country and forced the PUK not to support the referendum any longer. Although the 14 brigades remain officially integrated, they were called on and controlled by party leaders, not the ministry of Peshmerga. Since then, the process of Peshmerga reform stopped and the relationships between parties has continuously deteriorated. Making the situation worse, senior Peshmerga commanders and politicians of both parties know exactly what is at stake if unification were to occur. These authorities have been the sole beneficiaries of their own protection brigades, corrupt practices, and party dynamics, and they are not so willing to give up their power, especially to other parties. As a case in point, a senior PUK commander allegedly ordered an attack on the headquarters of the Gorran Movement in Sulaimaniyah in 2018 after the Gorran Party complained about vote violations and the results of the KRG elections. Clearly, any deviation from the divisive norm is a threat to party officials. Kurdish forces of Peshmerga. Photo @Levi Meir Clancy for Unsplash. Where Does the Aid Go U.S. support for the Peshmerga forces goes back to the 1970s, when the Peshmerga fought against the Iraqi government of Saddam Hussein and the U.S. supported them in order to deter Saddam from falling into an alliance with the Soviet Union. In 1991, the U.S. and its allies played a major role in establishing and enforcing a no-fly zone over northern Iraq. They supported the Peshmerga to serve as a local fighting force to stabilize the area after Saddam’s regime was overthrown. In recent years, the U.S. and its allies have provided financial aid, arms, and training to the Peshmerga forces in the name of countering IS. But U.S. support has not actually gone to the low-level Peshmerga soldiers who fight IS forces on the frontlines. Instead, senior party officers and high-level Peshmergas—individuals who have never faced IS—receive the funds and guns. I talked to two Peshmerga soldiers for this project, one from the PUK and one from the KDP. Neither soldier has seen any U.S. ammunition or weapons on the frontline, and instead, they fight with their own guns and bullets. The Peshmergas do not get any money back for these expenditures, despite the fact that they cost an arm and leg. When asked, the Peshmergas revealed that most U.S. guns go to senior commanders and their personal guards, who have never fought IS. These guns are used to shoot and kill the civilian protesters who request basic rights in the KRG, or for the protection of tribes—not for eliminating the IS threat. In addition, a portion of guns also goes to the bodyguards of some political and military seniors who look after their farms and gardens in suburban areas. At the same time, a number of guns provided by the U.S. are sold on the market illegally, at times even going to IS forces that are able to pay. Several members of the KRG parliament and journalists have verified that senior Peshmergas have traded weapons with IS. Nevertheless, these officers have not been charged. The United States Needs to Take Action The U.S.-Kurdish military action against Saddam Hussein’s regime and IS is one example of successful cooperation in the Middle East. Each side needs the other; the U.S. needs to exist in the area to protect its interests and stop the incursion of Russia, China, and Iran into the KRG. At the same time, the Kurds need the U.S. to protect themselves from extremist groups and threats from neighbouring countries. Furthermore, over the past 20 years, the U.S. has not had smooth relations with Shiite groups as they support Iran, while the Sunni groups have consistently clashed with American troops during the post-Saddam era. The Kurdish Peshmerga, in contrast, has consistently supported connections with the U.S. But in the last decade, the Kurdish leadership has taken advantage of the Peshmerga and continues to misuse their relationship with the U.S. This situation does not facilitate the U.S.’s regional interests and may force them to rethink other new partnerships and even to stop supporting the Peshmerga forces. But the U.S. should not cut off this relationship. In doing so, the U.S. may lose an epicentre of power in the region and cost the Kurdish authorities their long-standing security from militia attacks from neighbouring countries. If this happens, it will be the end of the Kurdish region of power, similar to the collapse of power in Afghanistan after the U.S.’s abrupt departure. Mahmoud’s most recent display with his private militia is only one link in a long chain of corrupt practices, personal brigades, and divisive tensions within the Peshmerga. To this day, Peshmerga forces remain loyal to their singular parties or party leaders, ignoring their stated purpose of protecting the Kurdish people as a whole and co-opting aid for themselves. By continuing with existing aid practices, U.S. officials fail to serve Kurdistan and its people. To change this reality, there are several steps the U.S. needs to take. First, they should push for abolishing the non-integrated PUK’s 70 units and the KDP’s 80 units—forces that only work for their parties. Second, the U.S. can curtail the KDP’s Zerevani forces and the PUK’s emergency forces, as well as the parties’ militia academies in Zakho and Qalasholan. Finally, the U.S. should investigate where the weapons and financial aid go and how they are used. Ideally, the Peshmerga must employ professionals in high positions who have no party affiliations. Without these steps and several more beyond, the U.S. support only helps parties and their corrupt politicians and commanders, not Kurdistan’s citizens. Diary Marif References: Van Wilgenburg, W. and M. Fumerton, “Kurdistan’s political armies: The challenge of unifying the Peshmerga forces” Carnegie Middle East Center, 2015. Arif, B. H. and T. M. Mokhtar, “The Kurdish civil war (1994–1998) and its consequences for the governing system in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq”, Asian Affairs, 2022. culturico https://culturico.com/2023/03/29/why-the-united-states-should-stop-supporting-the-iraqi-kurdish-peshmerga/

Read more'Iraq is not an Islamic country': Minorities protest Baghdad's alcohol ban as unconstitutional

The Iraqi government's renewed effort to prohibit alcohol is not only worrisome for Christian and Yazidi minorities, but also raises constitutionality questions. Draw Media, Al-Monitor Iraq officially banned the import, production and sale of alcoholic beverages of all kinds on March 4, in a repeat of a ban that was passed in 2016, but its implementation was paused due to strong objections from secularists and minorities at the time. The new law imposes fines for violations of between 10 million and 25 million dinars ($7,700-$19,000). Last month, the law instituting the ban was published in Iraq's official gazette, paving the way for implementation. The coalition of new Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani, who took office last October, is dominated by Shiite Islamist parties and militias in the so-called Coordination Framework who support the ban. Now, with the law going into effect, liquor stores are still open in Baghdad, Erbil and other parts of the country. But some Iraqis, especially those from the Yazidi and Christian communities, are raising concerns. 'Not an Islamic country' Iraq has great religious diversity. The majority of the population is Shiite and Sunni Muslims, but there are also sizable communities of Christians, Yazidis, Zorastrians, Mandaeans and others. Some analysts believe the law is a step toward turning Iraq into an Islamic country. "This is ethnic discrimination," Diya Butros, an activist in the predominantly Chaldean Catholic town of Ankawa, told Al-Monitor. "It's a violation of the rights of non-Muslim religions that do not forbid alcohol." Ali Saheb, an Iraqi political analyst, told Independent Arabia on March 6 that Iraq is not an Islamic country, and "Some religions allow drinking alcohol, and the government cannot impose a certain opinion or ideology on others." Unlike Islam, the Yazidi and Christian faiths do not forbid alcohol consumption. Some even use it in their religious rituals. Others argue the law violates the Iraqi constitution, which guarantees personal, religious and cultural freedom. Mirza Dinnayi is a Yazidi activist and chairman of Luftbrucke Irak, a non-governmental organization that helps victims of conflict in Iraq. He told Al-Monitor, "The law is contrary to the constitution because Iraq is a multi-ethnic, -religious and -cultural country, and drinking alcohol is not prohibited for many." Dinnayi also argued that if alcohol drinkers turn to other alternatives, the ban could provide an opportunity for the spread of drug use “The majority of Muslim countries do not ban alcohol, but rather regulate it. Why doesn’t the Iraqi government do something similar, instead of banning it totally?” The law is especially troublesome for Yazidis and Christians, who manage the overwhelming majority of alcohol shops in the country. Many Christians and Yazidis have been attacked in recent years for working in this sector, and some fear this law could lead to an increase in violence against them. It is therefore unsurprising that Iraqi civil society groups have come out strongly against the law. More than 1,000 prominent Iraqi researchers, academics, journalists and activists drafted an open letter to the secretary general of the United Nations earlier this month criticizing the ban. In addition to the objections on constitutional grounds, the autonomous Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in northern Iraq may reject the law. The Kurdistan Region is home to much of Iraq's Christian and foreign population, particularly in Ankawa and the nearby regional capital Erbil. A KRG customs official told the Kurdish news outlet Rudaw earlier this month that they reserve the right to make their own decision on the ban. Religious authorities' views The law is religiously motivated by the Islamic prohibition on alcohol, but Shiite religious authorities did not play a role in it. The highest religious authority for Iraq's Shiite majority, in the holy city of Najaf, is headed by Ayatollah Ali Sistani. Throughout the 21st century, Sistani has vocally supported a civil state and rejected the imposition of religion. Sistani has not commented on the law, but a prominent cleric told Al-Monitor that the religious authority in Najaf is against this legislation or any similar action. “The religious authority in Najaf has been always calling for a ‘civil state’ in Iraq, rejecting any kind of imposition of religiosity in the state institution,” he said, speaking on condition of anonymity. The source referred to stances taken by Sistani in the past, such as when he rejected the Personal Status Law in 2013 due to its imposition of Sharia, as well as the leader's rejection of displaying religious symbols in state offices. When asked about Sistani's current silence, the cleric said, “Sistani had made it very clear for a long time that he is against such a law, and there is no need to repeat the same thing.” With corruption and militia control rampant in Iraq, however, many worry that the ban will drive Iraqis to the black market to purchase alcohol. In this context, the ban may increase drug smuggling into the country, as well as encourage other forms of substance abuse.

Read moreReport Reveals Only One Million Iraqi Women Are Employed

According to this United Nations report, women’s participation rates in the global labour market between the ages of 25 and 54 increased in the 1990s to between 60 and 85 percent. Unfortunately, this has not been the case for Iraqi women, whereby women’s entry into the labour market is a huge challenge in Iraq. Increasing women’s participation in the labour force would improve the productive capacity of the country and support economic growth. In turn, this could help give women the ability to express their opinion in society and play a leading role in the family. To date, there is little research that explores the reason for the decline in women’s participation in the labour force in Iraq. Despite the importance of the subject, research that has been conducted is on a limited scale. The latest report in 2021 was conducted by the International Labor Organization, in cooperation with the Ministry of Planning, and the Central Statistical Organization. The report shockingly revealed that “there are 13 million women within the working age, of whom only one million are engaged in work.” Iraqi Women’s Participation in the Labour Force in Numbers Those aged 15 and older, who are of working age, account for 6.63% of the total population of Iraq. Men constitute 50.3% and women are 49.7% – almost half of the country’s population. Unfortunately, this percentage is not reflected in women’s participation in the labour force, nor in equal access to resources and opportunities. According to the 2021 Labor Force Survey in Iraq, the percentage of the labour force in Iraq reached 39.5% of the total population of working age. Men accounted for 86.6% while women were only 13.4%. The labour force participation rate for women was 10.6%, compared to 68% for males. These rates are among the lowest rates of female labour participation in the world. This significant decrease in women’s labour force participation is due to several reasons, including Iraq’s instability, a lack of culturally sensitive spaces, financial constraints, and a competitive job market with few jobs available. In addition to the unemployment rate, which reached 16.5% in Iraq, the above graphic shows that there is one unemployed person for every 5 people. On the other hand, the female unemployment rate reached 28%, which is double the male unemployment rate of 14%. According to the results of the Ministry of Planning / Central Statistical Organization, women tend to be more concentrated in the fields of services (73%) and agriculture (14%), compared to 62% and 7%, respectively, for men. The results also showed that the following sectors are male dominated: Construction and related professions Protection services Drivers of cars, trucks and motorcyclists Sales representatives While the professions dominated by women are: Primary education and kindergarten High school Garment industry and related professions As for the preferences of work sectors, 71% of women prefer to work in the government sector, while 29% of them prefer to work in the private sector. While for men, 34% of them prefer to work in the government sector and 65% of them prefer to work in the private sector. Steps to Expand the Scope of Women’s Work The World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report indicated that Iraq ranked 154 out of 156 countries in the Global Gender Gap Index for the year 2021. These numbers show the seriousness and importance of the issue. Unless real and decisive steps are taken to support women, Iraqi women will continue to fall behind. Institutions must work together to reduce the gap by developing female talent for the industries of the future. Additionally, the government must develop legislation for early marriage and childbearing, as is the case in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, which has placed women as a priority in the labour market, in both its private and public sectors, and in all aspects of life. Removing these disparities would reduce the unemployment rate, raise the level of women’s participation, enhance competition among jobseekers, revitalise the efforts of many vital sectors and ultimately grow the country’s GDP. In The End Women have an important and active role in society, and they represent half of it! Despite the limited opportunities and obstacles faced, many Iraqi women have proven that they can be successful and contributing members of society. But the question is, where does the problem lie in these statistics? The percentage of women’s participation in the labour market in developing countries, including Iraq, is less than the global average, noting that the percentage of women’s participation in developed countries is more than 67%. What Iraqi women need today is not limited to increasing available job opportunities, but we must also realise the many complexities and challenges that women face in the labour market. And as the data has highlighted, we need to facilitate women’s participation in the workforce by addressing social norms, establishing sound policies, and real commitment to implement these frameworks across the country. Today, we live in a rapidly evolving digital world where the digital economy can provide more opportunities for women to be involved in the workforce, and create new job opportunities that women can easily adapt to. This work has been done by the support of MiCT organisation and Germany cooperation GIZ Iraq.

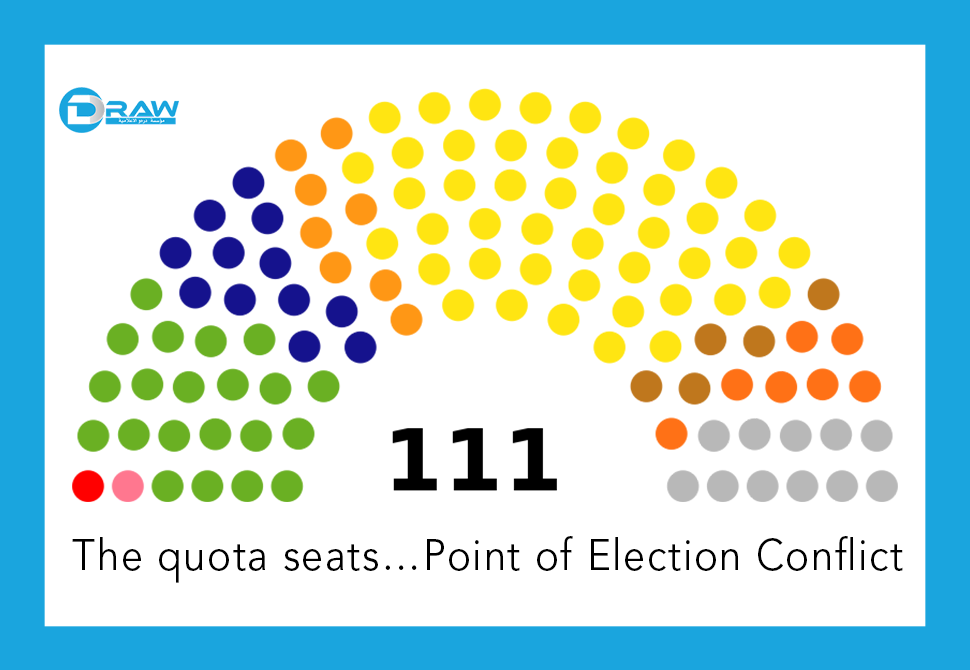

Read moreThe quota seats…Point of Election Conflict

Draw Media Religious and ethnic minorities quota seats have become the main problem facing the parties for the sixth session of the Kurdistan Parliament. Some are in favor of distributing the quota seats among the provinces. Others believe that the minorities’ representation in Parliament do not express their opinions and are monopolized by the political parties. The total number of votes obtained by the minorities in the first round of the Kurdistan parliamentary elections was (11 thousand 971) votes. In the last parliamentary elections, their total votes increased to 23 thousand 165 votes. The share of the minorities in the Kurdistan Parliament is one of the points of contention between the political parties and some call it the "The Knotty Spot of the elections." Some parties believe that the quota seats are monopolized by the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and in parliament, the representatives of the minorities decide in their interests. Therefore, some parties are in favor of dividing the quota seats among the constituencies, so that a Turkmen seat for Kfri district and a Christian seat for Sulaymaniyah province. In Iraq, 2.3% of the seats in the House of Representatives are reserved for some communities. But others have not been given any political opportunities. In the Kurdistan Region, 10% of the seats in parliament are allocated to the communities. These figures do not fully reflect the rights of minorities, since the voices of minorities are rising from time to time, they say that those appointed in parliament do not represent the communities. This is despite the fact that the Yazidis and Kakais, who are largely residents of the Kurdistan Region, have no representation in the Kurdistan Parliament. According to Article 36 of the Kurdistan Parliamentary Election Law No.1 of 1992, amended: First, five seats will be allocated to the Chaldeans, Syrians and Assyrians. Second, five seats will be allocated to the Turkmen. Third, one seat will be allocated to Armenians. Now the main point of disagreement between the political parties, especially the PUK, the opposition and the independents Now the main point of disagreement between the political parties, especially the PUK, the opposition and the independents against the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) is the distribution of community seats and voter registration for communities.

Read moreThe oil values in Iraq and the Kurdistan Region in 2022

Draw Media Based on Deloitte reports, compared to the data of the Iraqi Ministry of Oil and the measures of SOMO, the value of oil in (Iraq and the Kurdistan Region) and the (KRG oil through SOMO) in 2022 is as follows; 🔹 The average cost of a barrel of oil in the Kurdistan Region was more than (45.93) dollars and in Iraq (13.38) dollars, in other words (54%) of the revenue of every barrel of oil went to the cost of the process and in Iraq only (14%) was the cost of the process. 🔹 If the Kurdistan Region had sold oil at the price and cost of SOMO, then instead of (39.06) dollars per barrel, (82.16) dollars would remain, that is, instead of returning 5 billion and 709 million dollars to the government treasury, (11 billion) dollars would return to the government treasury. First, compare the oil prices of the Kurdistan Region and Iraq in According to the analysis, the Iraqi government in 2022, through the Iraqi Oil Marketing Company (SOMO) sold an average of $ 95.54 per barrel, the total value of oil sold was (115 billion 466 million 245 thousand) dollars. According to Duraid Abdullah, researcher and expert; “Foreign Oil Companies have 20% share out of 70% of the exported Iraq’s oil. "Iraq spent $16.1 billion last year on oil production," he said. According to this analysis, the return rate of Iraqi oil revenue was 86% and 14% went to the cost of oil processing. In other words, an average of $82.16 per barrel of oil sold returned to the Iraqi treasury and $13.38 was spent per barrel. But that is not true for the Kurdistan Region! According to Deloitte, the Kurdistan Regional Government in 2022, through the Kurdistan oil pipeline, sold an average of $ 84.99 per barrel and the total value of oil sold and delivered to foreign buyers (through the pipeline except domestic) was (12 billion 331 million 417 thousand 848) dollars and (90 million 843 thousand 46) dollars from domestic oil sales, but only (5 billion 709 million 704 thousand 87) dollars were put on revenue and the KRG General Treasury (Ministries of Finance and Natural Resources). Accordingly, the return rate of oil revenue was 46% and 54% went to the expenditure of the oil process. In other words, only $39.06 per barrel of oil sold in the Kurdistan region returned to the general treasury and $45.93 was spent per barrel of oil for the production process.

Read moreDraw Media publishes the KRG proposal and the response of the Iraqi Ministry of Oil regarding the oil and gas law

Draw Media According to a document obtained by (Draw Media), the Legal Office of the Iraqi Oil Ministry on 15/2/2023 have responded to the proposals of the Kurdistan Region regarding the oil and gas law and rejects 10 out of 15 suggestions. The proposals have not been directed to the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) delegation, but instead the legal office has submitted to the Iraqi Oil Ministry. The Iraqi Oil Ministry is against the KRG (selling oil, having its own oil and gas pipelines, having an oil and gas council, and reviving the KRG's oil and gas law after being repealed by the Federal Court). These are the details of the recent discussions between the Kurdistan Regional Government delegation and the central government on how to write the draft of the oil and gas law. The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) has presented its proposal on the law in 15 points. The central government has rejected 10 points of the KRG's proposals, which is 67% of the proposals. • Article 111 of the Constitution One of the principles that the Kurdistan Regional Government delegation in the negotiations to prepare the draft law on oil and gas submitted to the Iraqi Ministry of Oil, compliance with Article (111) of the Iraqi Constitution. Article 111 of the constitution states that "oil and gas in all regions and provinces belong to the entire Iraqi people." The Iraqi government agrees with the KRG, because it believes that this article of the constitution defines a good basis for the ownership of oil and gas and does not give any rights to either the central government or the KRG. Grant of permission The KRG has proposed that the issuance of oil licenses should be under the authority of the parties specified in the constitution, while the contracts for the fields in the Kurdistan region should be under the authority of the region, in accordance with Article 115 of the constitution. The federal government rejects the proposal, saying that the constitution does not give the authority to grant oil exploration and extraction licenses to any party, but in Article 112 writes that the federal government together with the Kurdistan Regional Government will manage the oil and gas extracted from existing fields. Transfer of ownership! The KRG has proposed that the oil and gas law allow for the “transfer of ownership of oil and gas to others at the point of delivery”. The central government disagrees with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) on this proposal, saying that such a provision cannot be included in the oil and gas law, because it is contrary to Article 111 of the constitution. The Iraqi government proposes to leave the regulation of the transfer of oil and gas ownership to the sales contracts signed for this purpose. Oil and gas policy The KRG has proposed that the Federal Council and the Regional Council for Oil and Gas Affairs take over the preparation of the strategic oil and gas policy. The central government opposes the KRG's proposal, saying it is unconstitutional and could open the door to the creation of councils in oil-producing provinces. Oil and gas policy The KRG has proposed that the Federal Council and the Regional Council for Oil and Gas Affairs take over the preparation of the strategic oil and gas policy. The central government is against the KRG's proposal, saying that “This proposal is unconstitutional and could open the door to the creation of councils in oil-producing provinces,". In addition, it will lead to a plurality of stakeholders responsible for setting the overall oil and gas strategy. Who should sell oil? The KRG has proposed that the region have its own marketing company and deposit crude oil revenues into an international account under the control of the region and the revenues from the sale of oil from the federal government into another account. The central government has rejected the proposal, saying it is contrary to the law regulating the Ministry of Oil and the rules of the oil marketing company. "The proposal also contradicts the provisions of the Financial Administration Law and the Federal Budget Law, which state that all revenues from the sale of crude oil must be deposited in an account opened for this purpose.

Read moreEnergy Geopolitics and Conflict between Energy Basins